Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

Police Must Inform Suspects of Their Rights

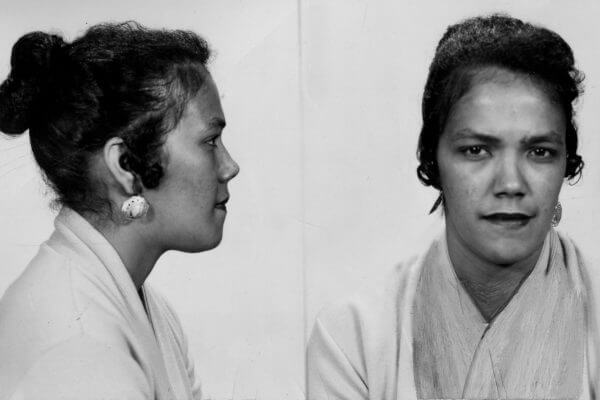

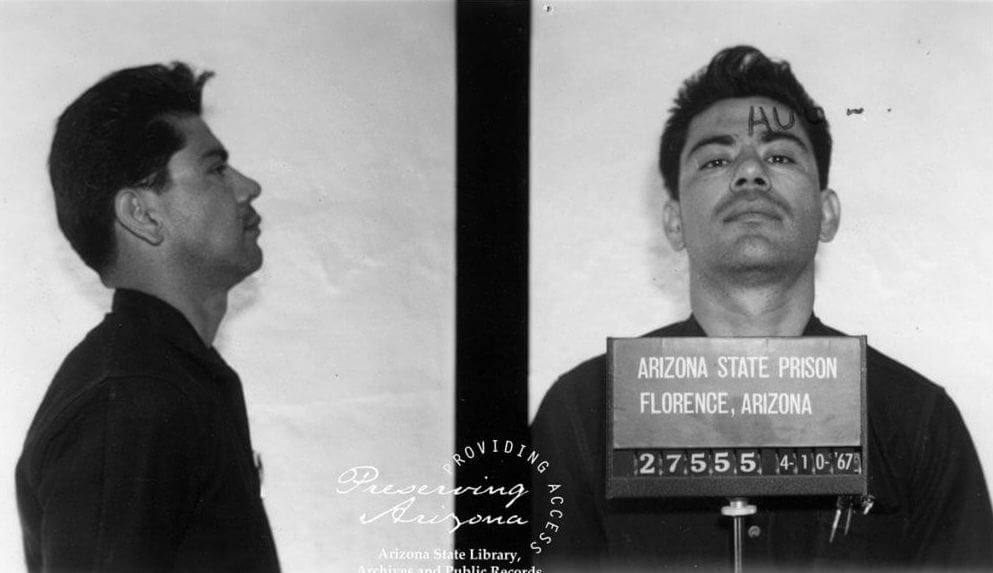

Mug shots of Ernesto Miranda, 1967

Photo Credit: Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, History and Archives Division, Phoenix, #00-0517

Overview

Ernesto Miranda was arrested after a victim identified him as her assailant. The police officers who questioned him did not inform him of his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination or of his Sixth Amendment right to the assistance of an attorney. He confessed to the crime, however, his attorney later argued that his confession should not have been used at his trial. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed, deciding that the police had not taken proper steps to inform Miranda of his constitutional rights.

Mug shots of Ernesto Miranda, 1967

Photo Credit: Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, History and Archives Division, Phoenix, #00-0517

". . . the prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from custodial interrogation of the defendant unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination."

- Chief Justice Earl Warren, speaking for the majority

Learning About Miranda v. Arizona

Students

This section is for students. Use the links below to download classroom-ready .PDFs of case resources and activities.

About the Case

Full Case Summaries

A thorough summary of case facts, issues, relevant constitutional provisions/statutes/precedents, arguments for each side, decision, and case impact.

Case Background and Vocabulary

Important background information and related vocabulary terms.

Learning Activities

After the Case

- Beyond Miranda

- Judicial Opinion Writing Activity: Dickerson v. United States (2000)

- Should the Miranda Warnings be Required Police Procedure?

- Unmarked Opinions Activity: Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004)

- Precedent and Stare Decisis

- Applying Precedents Activity: J.D.B. v. North Carolina (2011)

- Mini-Moot Court Activity: Florida v. Powell (2010)

- Document Analysis

Teachers

Use the links below to access:

- student versions of the activities in .PDF and Word formats

- how to differentiate and adapt the materials

- how to scaffold the activities

- how to extend the activities

- technology suggestions

- answers to select activities

(Learn more about Street Law's commitment and approach to a quality curriculum.)

About the Case

- Full Case Summaries: A summary of case facts, issues, relevant constitutional provisions/statutes/precedents, arguments for each side, decision, and impact. Available at high school and middle school levels.

- Case Background: Background information at three reading levels.

- Case Vocabulary: Important related vocabulary terms at two reading levels.

- Diagram of How the Case Moved Through the Court System

- Case Summary Graphic Organizer

- Case Summary Graphic Organizer - Fillable

- Decision: A summary of the decision and key excerpts from the opinion(s)

Learning Activities

After the Case

- Beyond Miranda

- Judicial Opinion Writing Activity: Dickerson v. United States (2000)

- Should the Miranda Warnings be Required Police Procedure?

- Unmarked Opinions Activity: Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004)

- Precedent and Stare Decisis

- Applying Precedents Activity: J.D.B. v. North Carolina (2011)

- Mini-Moot Court Activity: Florida v. Powell (2010)

- Document Analysis

Teacher Resources

Planning Time and Activities

If you have TWO days...

Note to teachers: We recommend that you invite a community resource person, such as a police officer, judge, or lawyer, to assist in the activities described here for day two. Many of the scenarios are tricky and the answers can depend upon the nuances of state law.

- Complete all activities for the first day (excluding the homework).

- On the second day, complete Miranda Warnings and the Bill of Rights to help refresh students' memories of how the Bill of Rights relates to the Miranda warnings.

- Complete Beyond Miranda

- For homework, have students read the Key Excerpts from the Majority Opinion and Key Excerpts from the Dissenting Opinion and answer the questions. Follow up the next day by reviewing the questions with students.

If you have THREE days...

Note to teachers: We recommend that you invite a community resource person, such as a police officer, judge, or lawyer, to assist in the activities described here for day three. Many of the scenarios are tricky and the answers can depend upon the nuances of state law.

- Complete all activities suggested for the first and second days (including homework).

- Complete the jigsaw activity Should Miranda Warnings Be Required Police Procedure?

- Complete Judicial Opinion Writing Activity: Dickerson v. United States (2000). To simplify, complete Unmarked Opinions Activity: Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004).

- For homework in advanced classes, complete Precedent and Stare Decisis. In on-level or middle school classes, complete Document Analysis: “Impeach Earl Warren” Postcard.

If you have FOUR days...

- Complete all the activities for the first, second, and third days (excluding homework on the third day).

- On the fourth day, conduct the Mini-Moot Court Activity: Florida v. Powell (2010).

- For homework in advanced classes, complete Precedent and Stare Decisis. In on-level or middle school classes, complete Document Analysis: “Impeach Earl Warren” Postcard.

Glossary

These are terms you will encounter during your study of Miranda v. Arizona. View all Glossary terms here.

Related Cases

Legal Concepts

- These are legal concepts seen in Miranda v. Arizona. Click a legal concept for an explanation and a list of other cases where it can be seen. View all Legal Concepts here.